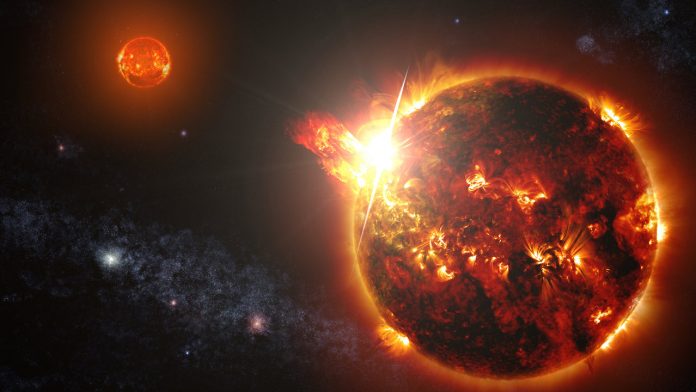

We see stars in pairs and triplets all the time in space. Three-starred Alpha Centauri is just one such example. But scientists never knew why stars so often come with companions. Did they always start off that way or did they tend to pull each other in later on?

Now a study from two researchers working out of Harvard and UC-Berkeley suggests sunlike stars are always born in pairs. The researchers came to their finding after taking a look at young stars inside a stellar nursery in the constellation Perseus.

Stars are born inside egg-shaped cocoons called dense cores. Normally, the cold grains of hydrogen dust comprising the cocoons make it impossible to observe the stars inside them. But last year, a team of astronomers were able to peek inside using the Very Large Array, a collection of radio dishes in New Mexico.

Using that new information, the study’s authors found that stars inside the cocoon aligned in a very particular way.

This does lend some credibility to one legend: that our own sun once came with a twin

Binary stars with a distance of 500 AU or more (500 times the distance of the Earth from the Sun) tended to be extremely young stars of less than 500,000 years and were aligned along the long axis of the egg-shaped core. Slightly older binary pairs were closer together, many separated by about 200 AU, and they didn’t necessarily align with the long axis.

This couldn’t have been random chance. Using mathematical modeling, the researchers concluded the only explanation that makes sense of the distribution is that all stars with a mass similar to our sun start off as binary pairs. As they grow up, 60 percent will split up while the rest tighten their orbit around each other.

“Within our picture, single low-mass, sunlike stars are not primordial,” said co-author Steven Stahler, a UC Berkeley research astronomer, in a statement. “They are the result of the breakup of binaries.”

We’ll still need further research to show whether the mathematical model can be observed in reality. But this does lend some credibility to one legend: that our own sun once came with a twin. More imaginative storytellers will go as far as speculating this evil twin – dubbed Nemesis – could have used its gravitational pull to punt the asteroid that ultimately killed the dinosaurs. Whether it really did that or not, what’s certain is it’s since sprung itself loose from its gravitational dance with our sun and made its own way out in the galaxy at large.