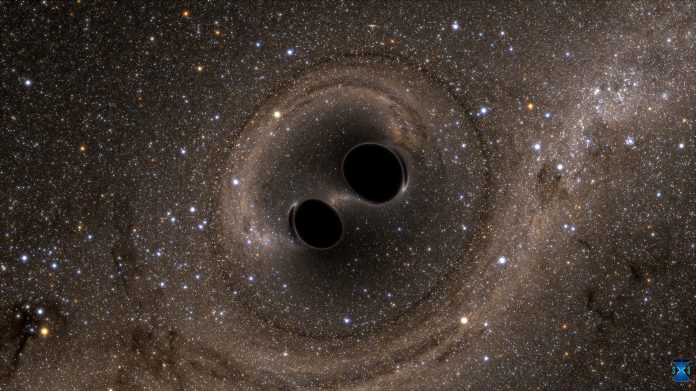

Yes, black holes can sometimes collide and last month marked the fourth time we’ve detected it ever happening. Nothing can escape the gravitational pull of a black hole – neither light nor sound. So scientists at the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) observed the phenomenon by measuring the resulting gravitational waves – ripples in the very fabric of time and space originating from the point of collision.

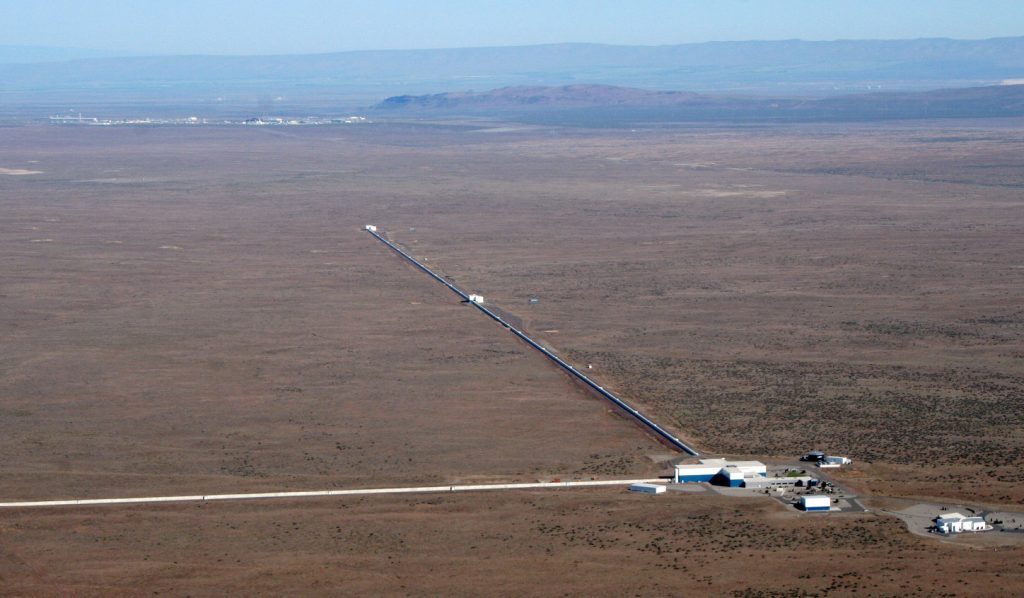

The National Space Foundation (NSF) which funds LIGO has two observatories in Washington and Louisiana designed to measure such gravitational waves. While both have picked up on such signals in the past, this was the first time a third observatory named Virgo and located near Pisa, Italy also picked up on the signal at the same time.

The benefit of three detectors working together means every observation gets that much better and scientists can pinpoint the location of the collision with greater accuracy.

“With this first joint detection by the Advanced LIGO and Virgo detectors, we have taken one step further into the gravitational-wave cosmos,” David H. Reitze, executive director of the LIGO Laboratory, said in a statement. “Virgo brings a powerful new capability to detect and better locate gravitational-wave sources, one that will undoubtedly lead to exciting and unanticipated results in the future.”

The collision was observed August 14th and the NSF announced the results last week. And their measurements of the size of the black holes speak to just how colossal an event this was. Taking place over billion light-years away, the collision involved one black hole with a mass about 31 times that of our sun and another about 25 times the mass of the sun. The cataclysmic event converted three solar masses into pure gravitational-wave energy and the final merged black hole ended up with a mass 53 times that of the sun.

Einstein was the first to propose the possibility of black hole collisions a century ago in his Theory of Relativity. In it, he also predicted we’d be able to detect their occurrence through the resulting changes to gravitational waves. Beginning with the 2016 publication of LIGO’s first observation from 2015, we’ve now proven Einstein’s theory a reality.

How black holes collide

There’s more than one way black holes end up colliding. In one scenario, they may start off as two supermassive stars orbiting each other in a binary system. Eventually one will die in a supernova and become a black hole. That stellar explosion is followed by the second. And over millions of years, two orbiting black holes will slowly but surely lose momentum and spin closer and closer together. Eventually, the fatal dance results in the two massive objects colliding and merging into one.

It’s believed all the galaxies of the universe have a supermassive black hole at their centers. This includes one at the center of our Milky Way galaxy thought to be more than 4.1 million times the size of the sun. Andromeda has one weighing in at a mind-boggling 110 to 230 million times the sun. And in a few billion years, our two galaxies are set to collide and merge into one. When that happens, the two black holes at our centers could also merge in one spectacular crash.