Biologist Hermann Muller was the first to discover just how much power we have to manipulate the genetic code when, in 1927, he blasted fruit flies with x-ray radiation in order to hatch mutant maggots. If genetic mutation is rare in nature, Muller proved man could artificially speed up the process by leaps. As he famously put it, “Mutation … does not stand as an unreachable god playing its pranks upon us from some impregnable citadel.”

We’ve come a long way since Muller’s experiments inducing changes to fly DNA. Now, one group of scientists at Temple University and the University of Pittsburgh just applied gene editing techniques to cure HIV in mice. Their findings are published in the journal Molecular Therapy.

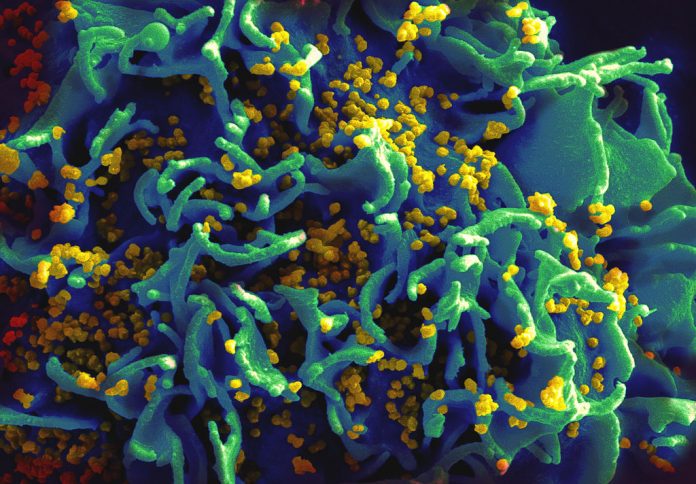

While research has come a long way in the fight against HIV and AIDS, a permanent cure still eludes us today. HIV patients currently take antiretroviral medications for their whole lives to suppress the virus’s spread. Why the virus remains so pervasive in the body is that HIV DNA will incorporate itself into the host’s DNA and hide itself in latent reservoirs around the human body.

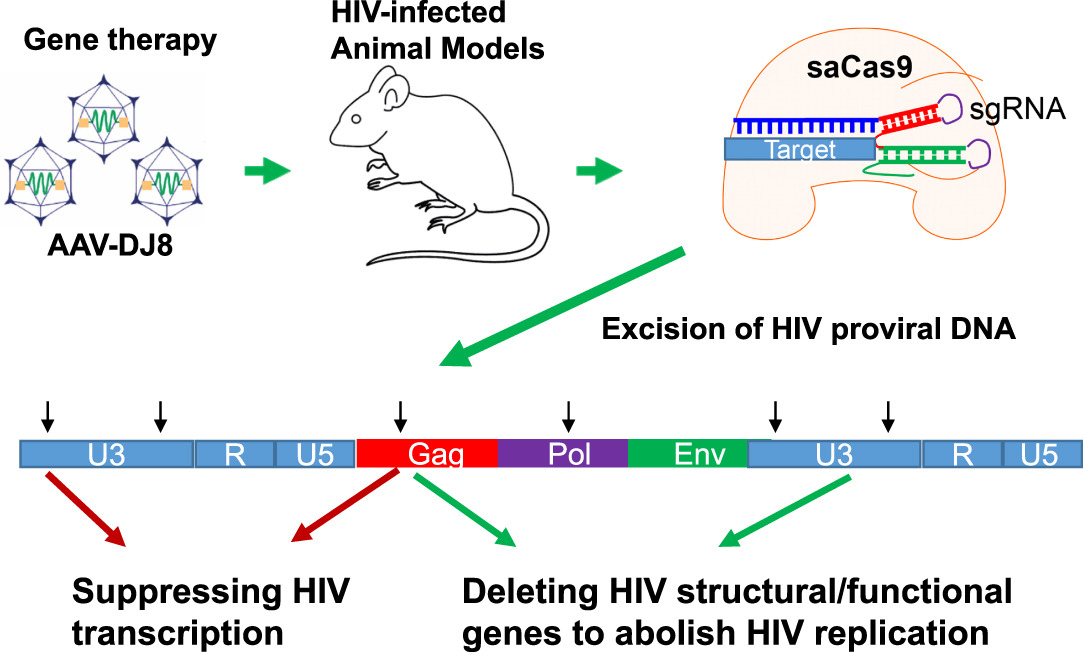

In the landmark study, researchers used CRISPR/Cas9 technology to snip out HIV-1 DNA from the mouse’s genome. A Cas9 protein was first injected into blood extracted from the subject. The protein would seek out HIV DNA and release an enzyme that removed it from the genetic sequence. After putting the blood back into the mouse, researchers found the RNA expression of viral genes reduced by 60 to 95 percent.

The study builds on a previous proof-of-concept study that the team published in 2016. It confirms data from the previous work and improves on the efficiency of the method.

“We also show that the strategy is effective in two additional mouse models, one representing acute infection in mouse cells and the other representing chronic, or latent, infection in human cells,” said Dr. Wenhui Hu, lead researcher on the study, in a statement.

With the success of the latest study, the researchers plan to apply the research on primates next. It may not be long before we’re ready to edit away the HIV virus from the world.

“The next stage would be to repeat the study in primates, a more suitable animal model where HIV infection induces disease, in order to further demonstrate elimination of HIV-1 DNA in latently infected T cells and other sanctuary sites for HIV-1, including brain cells,” said study co-author Dr. Khalili. “Our eventual goal is a clinical trial in human patients.”